Jolene, Jolene

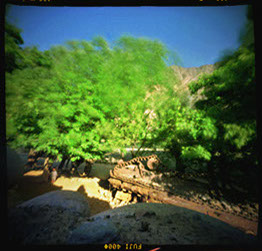

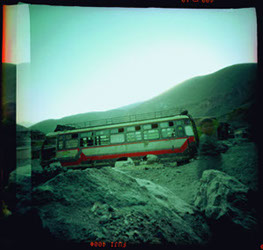

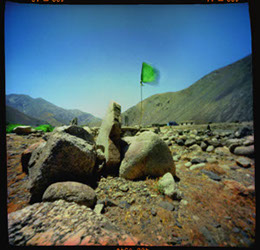

Soviet, Taliban, that’s one of ours, Soviet again… In a monotone Aziz recites a litany, naming the rusting tanks and mortars littering the fields. We bump along in the car. This is what we do, I thought, we humans. This is who we are. Aziz has the driver stop at a place where the mountains reach straight up from either side of the road, the cliffs nearly touching far above our heads. No one can get through here, he said. How far is Kabul? I ask. About thirty miles.

At night, usually around two o’clock, the boom of distant shelling echoes through the Valley. In the morning, at breakfast, I ask, What was it. Oh, comes the invariable, laconic reply, that was nothing. Just blowing up some empty houses in the mountains.

Aziz is made to live in a country at war like I am made to be an astronaut. How old is he? Thirty-five? Forty? Even the children look older than the age they claim, their faces lined and drawn. In July, 2001, what everyone in the Panchir Valley has in common is this: they are too poor to leave and too tough to die.

During the day Aziz wears a fixed look: alert, humorless, and authoritative. He is the kind of man one finds everywhere close to power, always around and no one knows exactly what he does. After we spent a few days together, he invites me to tea.

At home, I meet his young wife and a new baby girl. Holding the baby, he becomes someone else, smiling, speaking softly, blushing with pleasure as he looks into her eyes. His wife, looking on, throws a grin my way. A medium-sized woman exuding ableness and vitality, she has none of Aziz’s disabused weariness. I get the impression she is both a pal and a wife to him. They’re in it together.

Aziz shows me his class picture from Muslim University in northern India. In the picture he wears a big moustache like all the other men. Now he wears a beard cut so short it’s hardly like a beard at all. What did you study there, I ask. Engineering. So he can ride around in a car all day with people like me.

Engineering is something that is needed in the Panchir Valley. There is no electricity, no telephone, and no paved roads. To drive 10 miles takes three hours. As the car passes the ruins of the power station, Aziz says, Taliban bomb.

The wealthy and the privileged have their own gas-powered generators. The call to prayer is amplified, and the house we are staying in has electric lights. But when night falls, the surrounding village disappears completely into blackness.

Every few days it is possible to bathe with hot water. I fill up a bucket from the bathtub faucet, heat it on a charcoal stove in the adjacent room, then carry the bucket back to the bathroom where I crouch in the bathtub, pouring alternating cups of hot water from the bucket and icy water from the faucet over my head. On the intervening days, it’s just the cold water.

There is a toilet in the bathroom, too, but it’s not connected to plumbing. Flushing the toilet also requires filling a bucket. None of the Western visitors can figure this out, and the Afghans working in the house don’t flush the toilet for us. Within a few days of our arrival, the toilet and the bathroom become a vile chamber of shitpiles and urine and flies, and they just stay that way and get worse. In the morning, the first thing I do is pour a bucket of water down the toilet, waiting in the hall while it fills to get away from the smell. But one bucket a day doesn’t do much.

Jolene, Jolene… it’s the driver’s favorite song. He plays it again and again as he steers the Volga around flocks of sheep huddling across the non-roads. Jolene, Jolene. The rest of the lyrics are sung in Persian by a man the driver and Aziz call the Afghan Elvis Presley. He’s dead now, Aziz says.

Sometimes the refugee camp is located across the road from the Defense Minister’s house, another guy who, like Aziz, is close to The Leader. When a bomb falls on the refugee camp, it relocates to the same side of the road as the Defense Minister’s house. Mostly farmers live in this refugee camp. It’s the only way they can get away from the bombs falling on their farms.

As the car approaches the refugee camp, and almost before I can see it, we hear the clamor of children’s voices. They run up to the car, hundreds of them, it seems, shouting and smiling and holding out their hands, the bigger children carrying the babies as they trot alongside the car. There is another photographer in the car, a man, he’s never seen anything like it, he says.

We can barely open the doors to get out. I step into the crowd of happily shouting children. They are all filthy, too thin, dressed in rags, streams of mucus caked with dirt running from their noses and eyes, their skin covered with rashes. They ignore the male photographer who steps back, taking pictures of the scene until I ask him to stop.

Women visitors mean gifts, candy. I have nothing but my camera. To get the children to move away from the car we play Simon Says. The kids love this game. Then we get back in the car and drive away. The children run alongside the car, waving, smiling and laughing, even though there has been no gifts, no candy. They’ll take whatever they can get.

The girls’ school is situated on a bluff overlooking the village, a good strategic position. After class, I go to the math teacher’s house. The translator and I sit in the living room with her entire family. What do you hope for the future of Afghanistan, I ask. I want Afghanistan to be like Iran, the math teacher says. Democracy, but with Sharia law. And she would like to go to university. Women in Iran go to university, she says. Because of the war she hasn’t been able to finish high school. How old are you, I ask. Twenty-three years old, she says. Are you married? I ask. No. My fiancé is in London. What is he doing there? We don’t know. He gave money to the smugglers and left three months ago, but we haven’t had news from him since.

In the market, the carcass of a small unidentifiable animal hangs from a nail while the sun congeals the blood at the tips of its legs and the holes where its ears used to be. The liver and the heart hang from a thread of fat. No one can afford to buy this piece of meat, although in the house where we sleep, we eat mutton twice a day. I pass this carcass hanging from its nail day after day, slowly drying out as flies walk over it. Then it’s gone.

Walking through the village, two boys come up to me and ask me to come to their English class, just about to begin. When we turn up at the school, the teacher is surprised but welcoming. Unlike the math teacher’s school, in this class all the pupils are boys. The lesson for the day is A Phone Call to Mexico. The teacher writes this on the blackboard. His is the only book, lying open on his desk. The students have no paper or pencils.

“A phone call to Mexico” the teacher begins, and the students repeat the sentence together. The sound is like water falling down rocks. The teacher asks me to say “A phone call to Mexico.” I say A phone call to Mexico, and then the teacher talks to the students in Dari for a while. Then the class is over.

One night, after dinner, I sit talking with D., a young doctor with a Swiss NGO, in his room. He becomes hysterical. He can’t stop laughing or crying or talking. She can destroy me, he says over and over, She can destroy me. His group had come to Afghanistan with $20,000, a photographer, D., and the intention of setting up some kind of aid facility, they weren’t sure to what purpose. His days are spent driving around the Valley with the group’s president, a politician with plans to run for mayor of their town, trying to identify some need that hasn’t already been filled by another NGO. The widow and the orphan, the widow and the orphan, this is what I need, the president repeats, day after day. As D. tells me this, he hiccups with laughter, as tears run down his face.

The Valley is full of NGOs. Some seem to be very active, others no more than a sign at the side of the road. Our contact to The Leader is also president of an NGO. She comes from a prominent Afghan family who went to the West in 1978. Oh, you are with C., people say wherever I go. Did she bring the books? Did she bring the vitamins?

The NGOs are one of two kinds of economic activity in the Valley. The other is heroin, controlled by The Leader. Otherwise, the teachers, the doctors, Aziz, no one is paid, no one has any money, but they are able to get by on credit because they are under the protection of The Leader. The farmers and the artisans, the people who are not connected to The Leader, are starving.

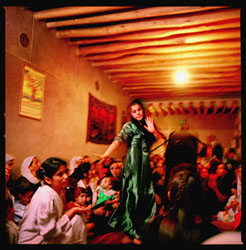

In a grove of trees by the river, a group of women take in the cool air at the end of the day. One of the women, massive and grand, seems to be in charge. A young man appears dressed all in white, down to a pair of very clean white Reeboks. He exchanges a few words with the women before introducing himself to me in excellent English. He tells me he has come to the Valley to go to a wedding, which is starting that night, and that the women invite me to come. Everyone in the village will be there.

Later that evening he comes to pick me up at the house. We walk through the pitch-black village, picking out the rocky path by the ray of a flashlight lent by C. At a house with fresh cement floors and cinderblock walls, he leaves me to go to the men’s party. The bride sits as still as a statue at one end of a large room packed with women, smiling slightly, her face a perfect mask, lips and toes and fingernails painted a matching dark red. Babies sleep in corners, music comes out of a boom-box. I recognize one singer as the Afghan Elvis Presley. Every now and then one of the women stands up to dance alone, turning and twisting slowly, dreamily to the music. Then she sits down again. The next morning at breakfast, C. says, Do you have my flashlight.

Jolene, Jolene. We bump along in the car. No one takes pictures of the things you do, no one has ever gone to these places, to the clinic, to the school, to the houses of the people, Aziz says. What do they take pictures of? I ask. They go to the front, they go to the prison, they talk to The Leader, then they leave. What about the women photographers? The women the same, he says.

The Leader comes to the house for an interview. The room chosen for the meeting changes several times throughout the course of the day, everyone rushing around carrying tables and chairs from one floor of the house to another. The entire day passes in this way. In the evening, the final location for the interview turns out to be the top-floor veranda behind the house, facing blank mountains. Not a single light glimmers on the mountainside.

Toward nine o’clock, a pristine black Toyota SUV skids to a halt in a cloud of dust in front of the house. The Leader, surrounded by men with machine-guns, races from the car to the house and up the stairs to the roof-top veranda as fast as he can. He sits down in a chair with his back to the house, facing the mountains. The group of journalists, sitting on the other side of the table, their backs to the mountains, are introduced to him.

The Leader is the most attractive man I have ever seen. He is dressed in bespoke khaki pants and jacket, pressed and spotless, cut in the safari style. The polished low boots gleaming on his feet also look handmade, not locally. When the interview is over the men with machine-guns take up positions along the staircase and around the Toyota. The Leader runs to it as fast as he can and the SUV tears off into the night.

A few weeks later he was dead, and two days after that, planes flew into the towers of the World Trade Center. My inbox filled up with terrified email from colleagues in India. “We are right next door,” one wrote, “We only hope Mr. Bush’s revenge won’t be too terrible.”

In October, on a television at the house of a poet in Mumbai, I watched the green streaks of the first American bombs fall silently on Afghanistan, while we spoke of other things. A few days later, watching the BBC report in my hotel room, I saw the young man who had taken me to the wedding, still dressed all in white and the Reeboks, ride into Kabul on a tank.

It seems Afghanistan has run out of Leaders, leaving only an eternity of seasons in Hell. With each change in the weather, the same stories return, year after year. In the Fall, there are the stories about the ever-growing poppy production, and the one about the horseback game played with the goat carcass. When snow blocks the roads, the reports are of negotiations with the Taliban and aid workers’ estimates of how many children will die from starvation, cold or lack of medical care. And with the return of Spring, the fighting.

In Paris, a quiet falls over the conversation as the afternoon light fades from the room. Fouad lights another cigarette. He sets down the lighter, picks up the newspaper, leaning back into the sofa. He laughs, puffing smoke, and turns the paper to show me the front page: “Did they make a mistake? This headline is from 10 years ago.”

Jeanne Hilary

Brooklyn, 2012